In the distant past of April 2020, Chris and I dove deep into an episode of our podcast Cinema Dual on the films of French filmmaker Agnès Varda. Though technically not my first experience with Varda, that week of watching Varda’s movies was eye-opening, to such an extent that when Criterion announced they were going to release a Blu Ray box set of her complete filmography, I jumped at the chance to catch up on everything I had missed. Each post will cover 1 of the 15 discs in the set.

At the time I wrote this, the first trailer for The Matrix Resurrections had just been released. I don’t care to speculate on plot details or the film’s ultimate quality, but I am interested in the ways the filmmakers reflect and reinterpret the franchise with almost 18 years of hindsight and growth. It seems to have at least some bearing on the plot, as Neo and Trinity struggle to remember their past together, but may also have stronger implications on the film as a whole. What does it mean for Lana Wachowski to go back to this particular subject matter now? And what did it mean for Agnès Varda to do the same with our next film?

Despite getting something of a career boost with Vagabond in 1985, Agnès Varda spent much of the 1990s in a more introspective mode, pursuing projects that looked back at film history and memories and how those interact, to mixed results. One Hundred and One Nights, despite being joyously and meticulously planned, seemed to leave critics mostly confused. Without implying any causation, it’s interesting to note the shift to shooting digital came after the perceived failure of one of Varda’s most elaborate film productions.

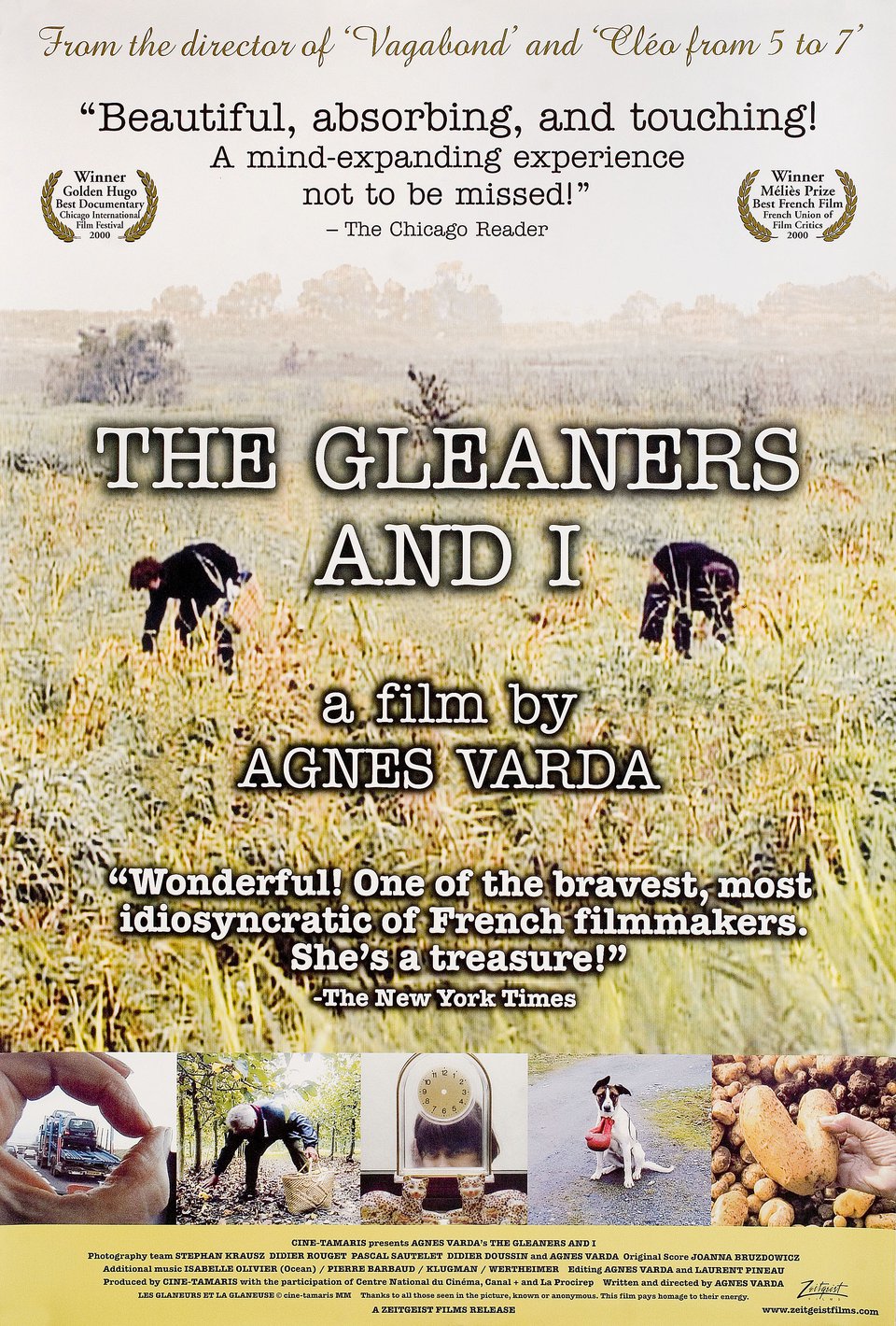

Armed with her Sony DVCAM DSR 300 and inspired by Jean-Francois Millet’s painting The Gleaners, Varda set to traveling across France to make The Gleaners and I (2000). In her travels, she talks to people who find and eat discarded food from farms and restaurants about how and why they do what they do. There are political dimensions to the stories of people are driven by necessity to glean as the act is known, and in so doing so evokes the drives of Vagabond. Varda has always been drawn to people on societies’ margins, and The Gleaners and I is no exception. Unlike Vagabond, the film’s subjects aren’t deliberately kept opaque, and are encouraged to speak their mind. It takes on a warmer, more open posture than that of its predecessor.

Varda also explores gleaning as a concept beyond its economic necessity for marginalized people. She brings in a lawyer to discuss how gleaning fits into France’s legal framework. Some of her interview subjects glean things like discarded food or appliances out of philosophical principles in order to not contribute to their societies’ waste. Varda draw a parallel to her own life, ruminating on the idea that as she gets older gleaning through her various personal possessions helps remind her of who she is and what she has done.

Varda credits the switch to digital as the inspiration for shooting the film, and the effects are noticeable. The Gleaners and I isn’t just about the people Varda meets, but about the filmmaker as protagonist, traveling to meet their subject. The result is Varda putting herself on camera more than any film so far. Shooting digital also allowed her to allow for happy filming accidents, like the notable Dance of the Lens Cap. The process of traveling, shooting a lot of material, then going back to edit, is itself a type of sifting, of gleaning, and probably the most notable example to date of Varda’s trusting to chance in her art.

Her instincts paid off, as the movie is almost universally beloved. Varda received such a outpouring of support from critics and fans that she shot a follow up movie titled The Gleaners and I: Two Years Later (2002). She attempted to catch up with as many of her subjects as she can, while also reflecting on the success of the original film. The idea of seeing how her subjects fared in the wake of the original has merit, but the result is somewhat anti-climactic, as most people report their lives not having changed much in the intervening two years. Even the people who bring up concerns about their portrayal in the original film don’t seem that bothered by it. As a bonus feature on the DVD of the original film for hardcore fans, it’s perfectly fine. As its own film, it’s more a curiosity than anything else.

When I initially set out on this project, I had a hunch that The Gleaners and I was the big blind spot that I was most looking forward to erasing. What I didn’t expect was a film that, beyond being quite moving and successful on its own merits, would tie together so many elements from across Agnès Varda’s career, both past and future. While there’s conversations to be had about her “best” film, or someone’s “favourite” Varda film, Gleaners feels to me like the most representational work of her career. If someone were to say “what is Agnès Varda about?” I would point them towards this movie.

Next time: Visual Artist

-Jon

Leave a comment