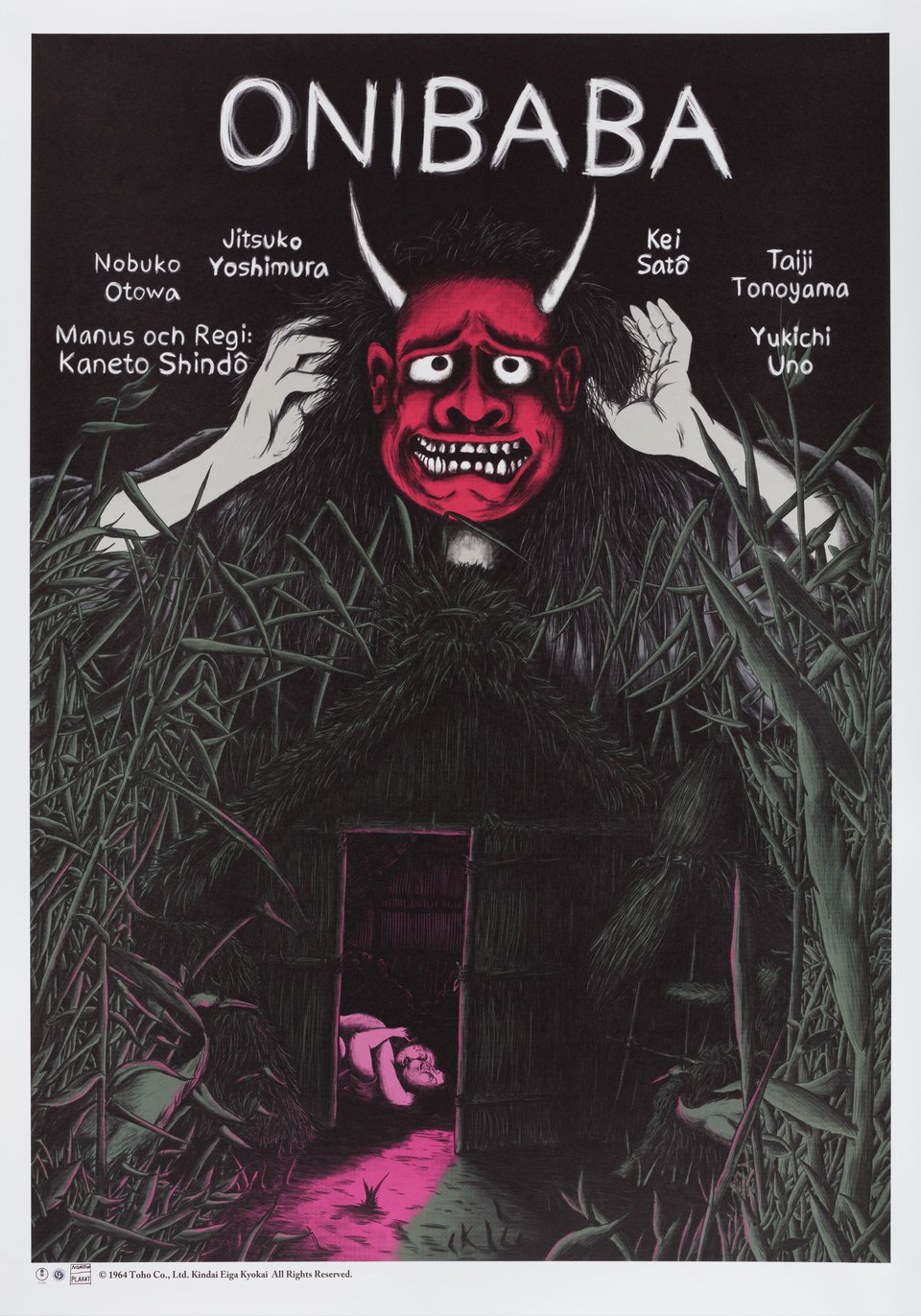

Being Film #31 for Hooptober 2024

Just incase you thought the sixties were only happening in the United States from a film perspective, change and rebellion was happening everywhere, particularly in Japan. Onibaba shows a very different side from what artists like Kurosawa and Ozu were doing within the confines of a studio system they grew up in. Writer/director Kaneto Shindō may seem at first impression to be working in a more exploitive frame – and you’d be right. But there’s more beneath the surface of this sleazy horror gem that ties in nicely with some of the other films watched during this marathon. As as the “official” capper to the marathon (there’s still the bonus films I’ll cover over on Letterboxd), it’s a fine ending to the start of a new decade of expanding my personal parameters of horror.

THE QUICK SUMMARY: A older woman and her daughter-in-law live in a dilapidated old house in the middle of massive fields of reeds, waiting for their son/husband to return home from war in medieval Japan. There’s an old hole there too, filled with the bones of soldier the women led to their deaths so they can sell the armor and weapons for food. When a neighbor returns home with the new their son/husband is dead, grief and lust ignite as the two women the fight over the man and their future survival. When a spooky samurai with an even spookier mask enters the picture, things turn mean and dirty as folklore supernatural horror mixes with desperation and jealousy for a fable ending you only get a film as weird as this.

My first thought watching Onibaba was how tactile a film it is. Shindō continued making films until his 90s, and I can imagine how delighted he would have been had he the advances in sound design back when he was making this film. His camera really focuses on the reeds that serve as the primary location of the film, and of the flesh of his characters, whether it’s feet dragging through broken reeds as the women carry dead soldiers to throw into the pit, or the sweat that marks every inch of their bodies – bodies Shindō is only too happy to show as the film moves on. So yeah, it’s a sweaty, sexy movie; visceral and humid, accentuating the frustrations and passions of the older woman and daughter-in-law. Their never given names in the film -that only belongs to the men, whether it’s the salacious merchant Ushi or the filthy Hachi, returned from the war without the pair’s beloved Kishi and the source of the film’s turmoil.

Is that intentional? I think so. A lot of the struggle displayed in Onibaba comes from both women’s pent up urges and desires, and whether they should be fulfilled, as well as how they’re perceived by the men in the film, which is merely sex toys, only there to fulfill the desires of men. It ties in nicely with the visual aesthetic and its lack of any remove from the action.

And for the majority of its runtime that’s all Onibaba is. It’s not until the last 15 or so minutes of the film that the horrific elements of the film come into play with the lost samurai and the mysterious mask he wears. Even then it’s used as a device for revenge, and it’s not until the very end of the film that the money’s paw of it all comes into play. So the film also brings into question what kind of film this actually is. Is it horror? Thriller? Exploitation?

Doesn’t matter. It’s all those things and whatever we bring to it as well. Just like any great film.

Leave a comment