Something Like a Filmography takes a (brief) look at the filmography of Akira Kurosawa. Twice a month, Chris and Jon share their impressions of each film, both on its own terms and in terms of Kurosawa’s legacy and its intersection in the Cinema Dual hosts’ lives.

FROM THE BOX: Toshiro Mifune is unforgettable as Kingo Gondo, a wealthy industrialist whose family becomes the target of a cold-blooded kidnapper in High and Low (Tengoku to jigoku), the highly influential domestic drama and police procedural from director Akira Kurosawa. Adapting Ed McBain’s detective novel King’s Ransom, Kurosawa moves effortlessly from compelling race-against-time thriller to exacting social commentary, creating a diabolical treatise on contemporary Japanese society.

WHAT CHRIS THOUGHT: One of my favorite directors, here adapting one of my favorite writers. If High and Low does nothing else, let it at least introduce you to the many joys of Ed McBain and the 87th Precinct series, of which the novel King’s Ransom serves as the basis for this film. But it should do much, much more. In some ways just as ambitious and experimental as any of his “greatest” works, Kurosawa masterfully mixes the high drama of the crime thriller with the burgeoning police procedural, using his camera and framing to reinforce there different sections and tones. Having watched Mifune grow over the course of nearly 15 years since Drunken Angel he brings all his age and wearied experience to bear as Gondo, the shoe executive caught in the middle of a hostile takeover of his role on the company board just as a mixup with a kidnapping threatens his entire livelihood. It’s his greatest role to date, and seeing him wrestle with his responsibilities to his family, his honor and ego surrounding his pride in his work ethic against his guilt over the kidnapping of his chauffeur’s son is a marvel.

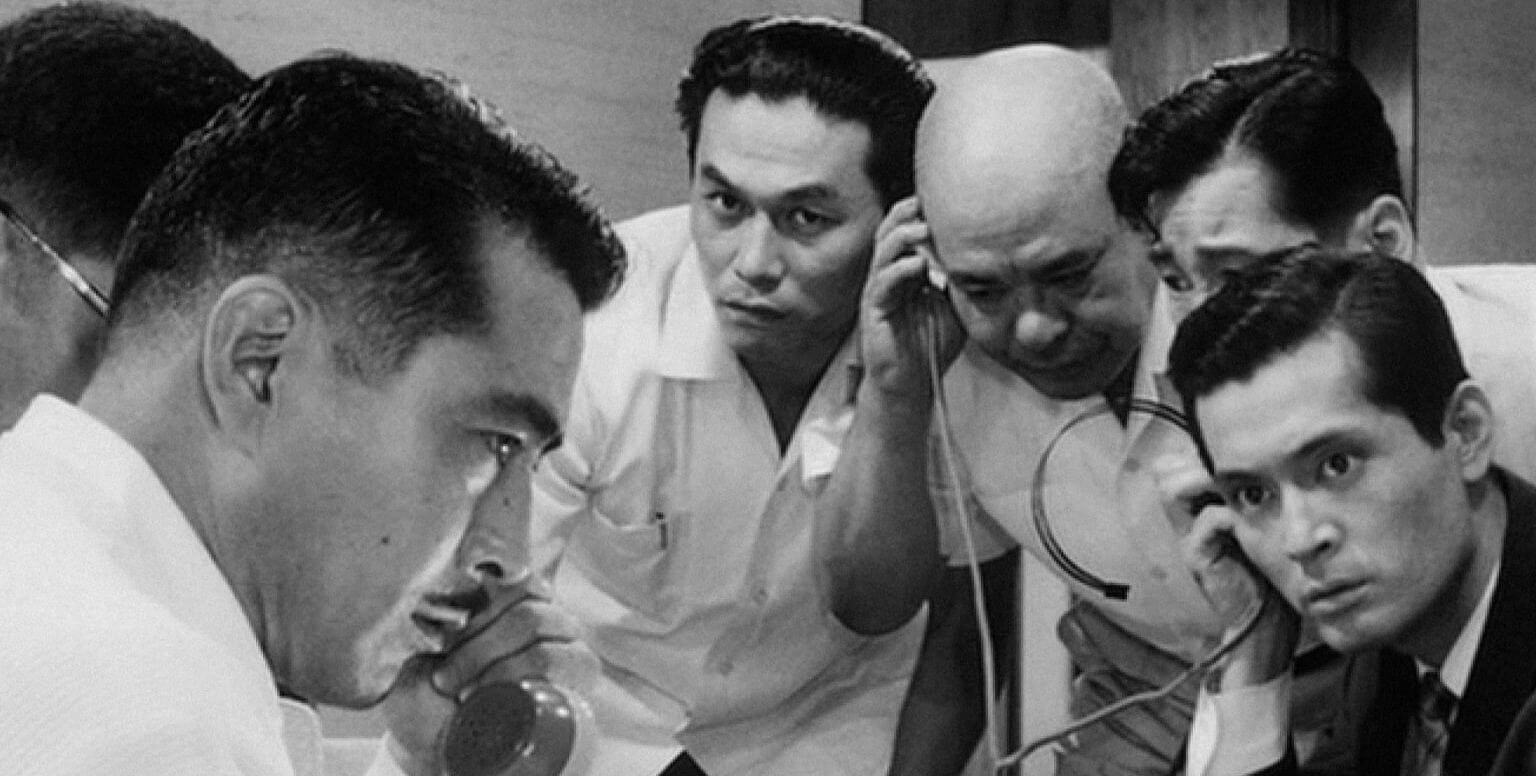

When the film switches into procedural mode, it’s another beast entirely, and just as excellent. Though my beloved Takeshi Shimura doesn’t appear until after the hour mark, Kurosawa invests just as much energy in his police squad, and much as I love the first half, it’s here where High and Low truly shines. Besides trying to find the parallels between Kurosawa’s squad and McBain’s characters, it’s fantastic to see Tatsuya Nakadai step out of the villain roles from Yojimbo and Sanjuro and into the lead detective spot here. He’s fantastic, but in keeping with the spirit of the novels Kurosawa truly makes the investigation and capture of the kidnapper (now also a murderer) a full group effort. Each viewing brings it further up in my estimation, and now High and Low is sitting comfortably in the #3 spot, topped only by Ikiru and Seven Samurai.

WHAT JON THOUGHT: Of High and Low‘s many, many achievements, for me the biggest among them is the casting. In the first half of the film, Toshiro Mifune reigns in some of his more exaggerated qualities from the samurai films without sacrificing any of the qualities that make him so magnetic. The range of emotions that Mifune takes you through as the script methodically grinds away at his desire for safety and comfort is considerable. And when he does finally make the crucial decision to pay the ransom, it feels earned.

But the second half of the movie is where Kurosawa really shows how deep his bench goes. Tatsuya Nakadai, underused in Sanjuro here gets to shine as Tokura the chief investigator, a much more straight laced character that shows the man has range. Also on the police squad are Takashi Shimura (again, underused but grateful he’s here), and my new favorites Kenjiro Ishiyama and Isao Kimura as Detectives Taguchi and Arai. Ishiyama is great as the gruff no non-sense cop and Kimura is quite stunning as the younger partner. I would watch a buddy cop movie with just those two. While Tsutomu Yamazaki’s turn as Takeuchi, the main villain, is mostly effective by virtue of those amazing sunglasses he wears, his monologue at the end where he regrets nothing, gives no motive and is seemingly willing to walk backwards into hell is quite chilling. When a scene that retells the audience a list of every lead being chased down is that exhilarating, you know you have something special.

ANYTHING ELSE, CHRIS? This is the first time I noticed how cinematographers Azakazu Nakai and Takao Saito use different lens and cameras to differentiate the action. Almost all of the first half is very static, filmed using long lenses to give a sense of distance and coldness to the calculations of the shoe company board and the machinations between them and Gondo to wrest control for themselves. During the second half when the police investigation begins in earnest the camera becomes much more dynamic: the scene as the squad follows Takeuchi, the kidnapper as he goes through the streets to the jazz club is a lesson in camera fluidity as each officer takes a piece of the surveillance. When Takeuchi arrives at the junkie’s den it’s almost a horror film, more terrifying than anything Kurosawa ever filmed, the junkies resembling the zombies that would arrive at the farmhouse just a few short years later in Romero’s cult classic.

But the real gem is the scene on the train, as Gondo receives directions as to how to transfer the money to the kidnapper. Shot in one take (not one shot, to be clear) using multiple hand held cameras, it’s the thrilling and high-energy connective tissue between the two sections of the film, standing as a stark reminder that Kurosawa could literally do anything with his camera and make the images with each other, even as they seem so different taken separately. Just stunning, and perhaps my favorite sequence in the whole film.

ANYTHING ELSE, JON? Since our initial thoughts overlap significantly already, I will simply say I also echo Chris’s thoughts on the cinematography. The handheld sequence on the train is absolutely the highlight, however we also get an iconic first for Kurosawa, his first use of color in the shot of pink smoke that comes from the furnace where Takeuchi burns the briefcase. In the context of movie, the use of pink smoke elevates a good plot payoff to stunning. In the context of Kurosawa’s career, where he already has built a multifaceted body of work, it hints at even more creative depths to explore, albeit not for several years.

THE FINAL WORD(S): For Chris this is pinnacle Kurosawa, a masterwork of tension and thrills, and perhaps home to the greatest Mifune performance. For Jon, this stands toe to toe against the best of Kurosawa’s samurai films.

NEXT TIME: We come to the end of Kurosawa’s “classic” unfettered period with the epic Red Beard, his final film of the 1960s as well as the end of his association with Toshiro Mifune.

Leave a comment