Something Like a Filmography takes a (brief) look at the filmography of Akira Kurosawa. Twice a month, Chris and Jon share their impressions of each film, both on its own terms and in terms of Kurosawa’s legacy and its intersection in the Cinema Dual hosts’ lives.

FROM THE BOX: When a warlord dies, a peasant thief is called upon to impersonate him, and then finds himself haunted by the warlord’s spirit as well as his own ambitions. In his late color masterpiece Kagemusha, Akira Kurosawa returns to the samurai film and to a primary theme of his career—the play between illusion and reality. Sumptuously reconstructing the splendor of feudal Japan and the pageantry of war, Kurosawa creates a historical epic that is also a meditation on the nature of power.

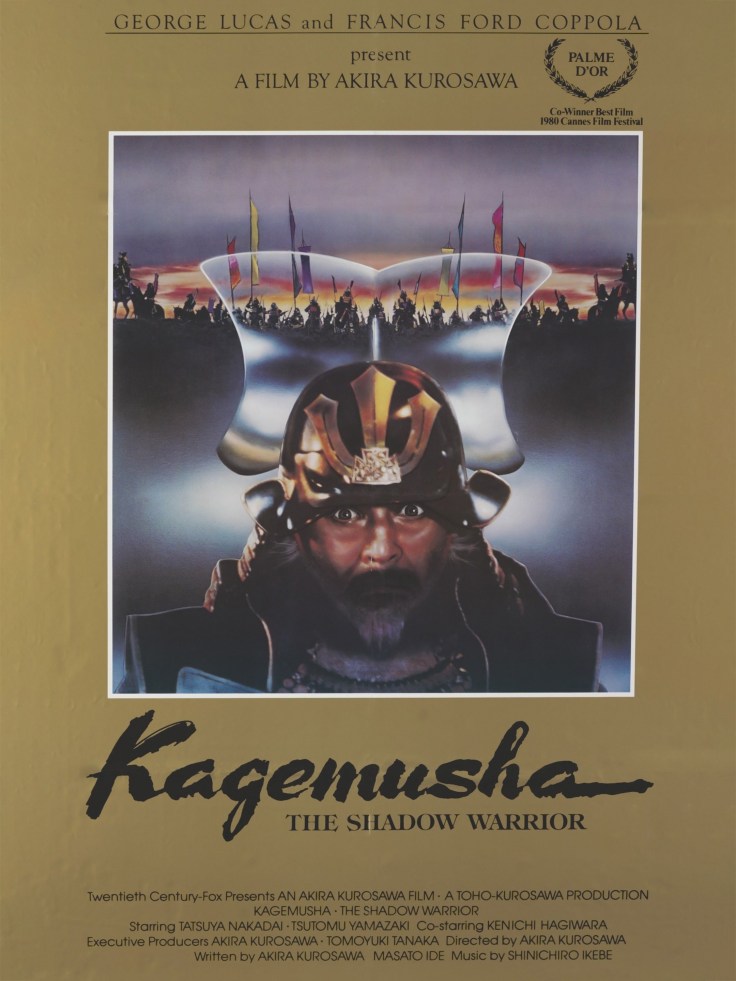

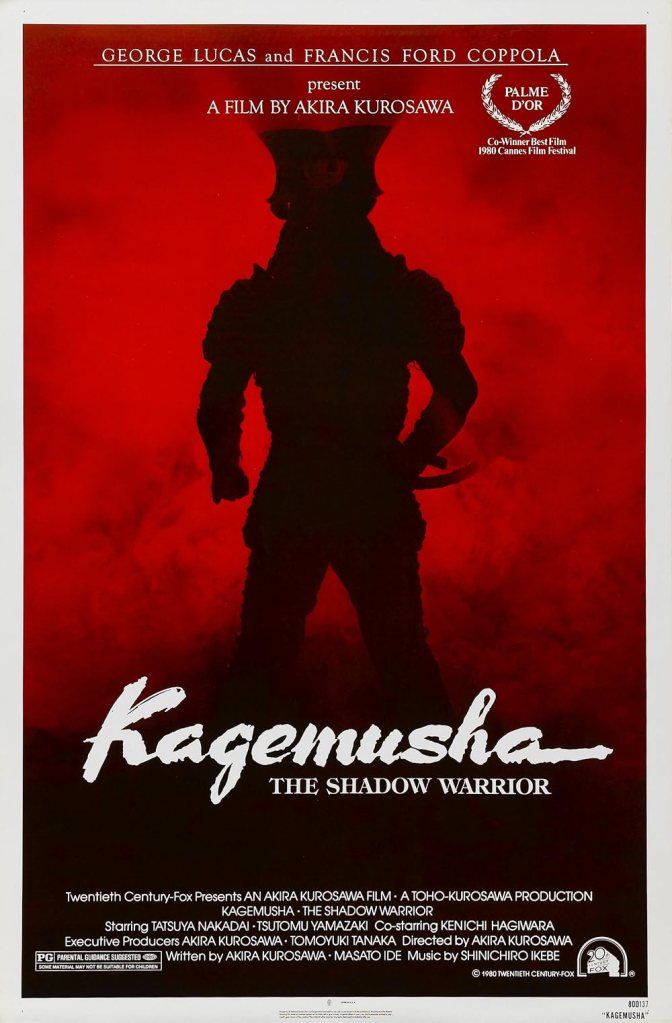

WHAT CHRIS THOUGHT: After spending the 70s in the wilderness (literally, in the case of the wonderful Dersu Uzala) Kurosawa, with a little help from his friends George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola returns full force to the epics that made his name. But much more than another samurai epic, Kagemusha drips with Kurosawa’s humanity and life, feeling intensely personal. In the flow of the narrative, where the Lord Shingen’s decoy, a thief of humble origins (Kagemusha translates to “shadow warrior”) reluctantly takes up the role full time once the Lord dies, we see Kurosawa wrestle with his own mortality, his talent and value in a world that seems to view him as an afterthought, and his seemingly perennial challenge of class.

And Kurosawa does this personal film in the most sweeping, gorgeous of ways. After experimenting with color in Dodes’ka-den and stretching it thanks to the forest locations in Dersu Uzala, here he absolutely masters it. Over the course of the three films his aspect ratio gradually opens back up, and seeing how Kurosawa’s bright, vibrant colors work against the 1:85:1 ratio is breath-taking. It’s a stunning mix of gritty realism and absolute fantasy, with thousands of extras and practical sets mixed with a surreal mix of colors that match mood and tone more than setting.

From a casting perspective Tatsuya Nakadai is phenomenal, certainly no surprise for those that know his work in earlier Kurosawa films or his incredible collaborations with Masaki Kobayashi. But tackling both the role of Lord Shingen and the decoy he’s a revelation, creating not two distinct characters, but many as the decoy moves through his arc. It takes two hours, but my beloved Takashi Shimura makes a small appearance, his last in a Kurosawa film, and it was such a joy to see him I stopped, took a picture and send it to Jon. It also marks my one small complaint with Kagemusha: while I love the unfettered imagination and budget on display (thank you Lucas and Coppola!), at just over three hours this feels long. There was one scene that is simply Katsuyori, Shingen’s hot-tempered son and heir, riding his horse around the courtyard three times. I have no idea why three times, but it’s one indicator that some editing down would have helped the momentum a bit.

WHAT JON THOUGHT: Kagemusha finds Kurosawa returning to his most well known genre armed with new perspectives offered up by his age and new filmmaking techniques. Whereas Dersu Uzala made splendid use of the natural colors found in the Siberian forest, here Kurosawa deliberately makes use of bright colors to represent the various warring factions. In line with his recent work, the pacing feels more contemplative, inviting viewers to soak in the visuals instead of dazzling them with fleet camera movements and quick edits.

The story concerns the cover up of the death of a daimyo Shingen by using a decoy who happens to be the spitting image of Shingen, both played wonderfully by returning favorite Tatsuya Nakadai. The attempted deceit of getting Shingen’s decoy to learn and act the part provides much of the movie’s plot. It also coincidentally inspired me to utter the phrase (surely the first time in human history), “Hey, this is just like that movie Dave.”

Initially wary of his assignment, eventually Nakadai becomes a true believer in the cause he’s trying to further, only to be frustrated, and inevitably exiled once the truth is discovered. While the Takeda clan’s plan is built on dishonesty, the lie does seem to work for a time, and it’s only when the lie is discovered that Shingen’s son Katsuyori takes control of the clan, and disregards his father’s instructions to the ruin of all. Kurosawa, long distrustful of the romantic heroism surrounding samurai, finds at least some use for it here, with a warning against ignoring the advice of one’s elders, which at this point in his life, increasingly includes himself.

ANYTHING ELSE, CHRIS? Can we talk about the incredible framing in this film? And I’m not talking about the massive scenes, like the incredible sequence of the muddy runner barreling through the armies, all segmented by different colors. Or the bravura dream sequence Jon mentions above, which takes Kurosawa’s painting expertise and splashes it on the largest canvas possible. Those all look fantastic (truth be told, I’m still wondering how they framed it so you can see Nakadai’s reflection in the pool even though he’s so far back). For me it’s the exquisite smaller moments, like how Kurosawa uses the screen doors to frame an early sequence where Lord Shingen laments to one of his generals that his allies are tiring and retreating from the battlements. Using the white room and then the screen doors opening and closing to bring in the greens of the outdoors is lovely, and combined with how expertly Kurosawa uses color is a masterful scene.

Similar but with more emotional heft is when Nobukado, Lord Shingen’s brother and the mastermind behind the ruse, presents the decoy’s staff to him. Aligned not only by station but by color, they lined up like chess pieces across the lined mat that serves to clearly delineate the scene. When Nobukado leaves the room, the camera moves to the back of the room to allow the camera to capture this sublime synchronous movement as all the servants – Nakadai’s decoy included – turn at an angle to bow at his departure. This might be my favorite scene in the movie, as the movements and emotions (the pages cry at seeing Nakadai expertly mimic their deceased lord) are choreographed like a ballet.

ANYTHING ELSE, JON? My only real problem with Kagemusha is Kurosawa will overshadow it almost immediately with his next film Ran. Ran covers similar themes, genres and techniques as Kagemusha but the colors are brighter, the big battle scenes are actually shown versus mostly implied. The societal and familial discord of Ran are more developed and in a shorter runtime than Kagemusha. This might not entirely be fair to Kagemusha, but as they are so similar and made in such proximity to each other, the comparison inevitably gets made. It’s still good, but just gets outpaced by its successor.

The obvious exception to the above is the psychedelic dream sequence in which the imposter realizes that he cannot be the daimyo no matter how hard he tries. There is nothing in Ran or anything else in Kurosawa to my memory that tries to do something like that. It is the film’s crowning moment.

THE FINAL WORD(S): For Chris, Kagemusha is a late period classic, vividly imagined and stuffed with rich allusions to the master’s life. Jon, Kagemusha is a solid samurai epic, that only suffers in the wider context of Kurosawa’s career.

NEXT TIME: Once more ’round the ramparts, for samurai, for Shakespeare, for the 80s. We go to Ran.

Leave a comment