Something Like a Filmography takes a (brief) look at the filmography of Akira Kurosawa. Twice a month, Chris and Jon share their impressions of each film, both on its own terms and in terms of Kurosawa’s legacy and its intersection in the Cinema Dual hosts’ lives.

FROM THE BOX: THERE IS MAN AND BEAST AT NATURE’S MERCY. THERE IS AWE AND LOVE AND REVERENCE. AND THERE IS THE MAN CALLED…

A military explorer meets and befriends a Goldi man in Russia’s unmapped forests. A deep and abiding bond evolves between the two men, one civilized in the usual sense, the other at home in the glacial Siberian woods.

WHAT CHRIS THOUGHT: After the confused and overwrought melodrama of Dodes’ka-den I’ll admit I wasn’t looking forward to the next entry in Kurosawa’s “lost” years, especially after the master’s attempted suicide and loss of confidence from the Japanese film industry to fund his film ideas. I lead with this to emphasize just how beautiful and lovely Dersu Uzala is. Forced to work with new collaborators under the watchful eye of the Russian studio, Kurosawa crafted a gorgeous film that embodies many of his preoccupations: aging, the conflict between social strata, and the relationships between people. Taken from the 1923 memoir, the film sticks to the broad strokes of a Russian military man tasked with surveying the far east of the country and the incredible friendship he forms with Dersu, the Goldi hunter and guide. Over the course of years they come together to face the dangers of the wilderness, learn from each other, and form a bond that death can’t tear asunder.

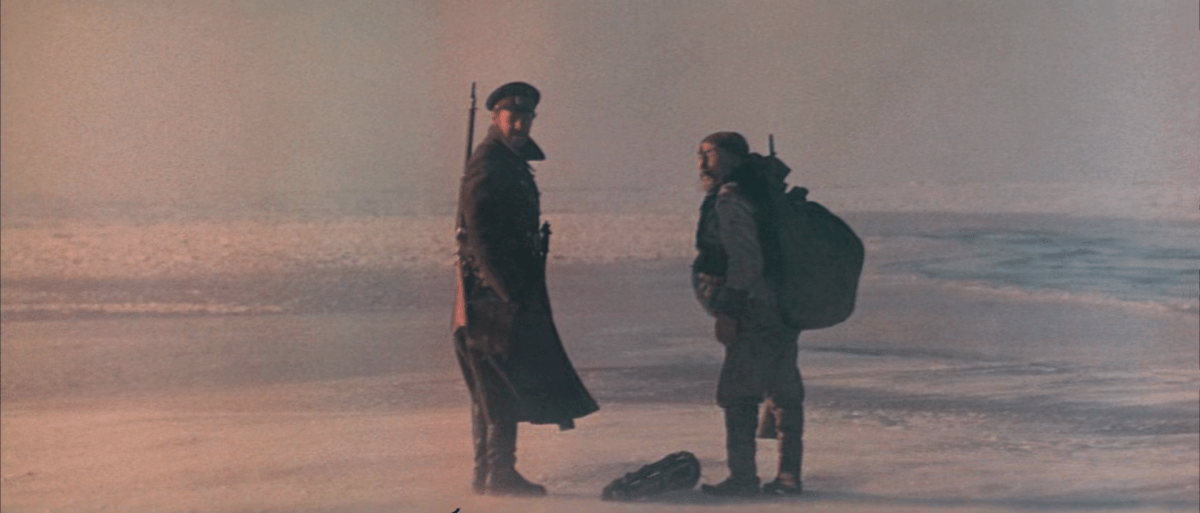

Visually it’s stunning, and if ever there was a Kurosawa film that needed a beautiful 4k restoration it’s this one. Largely filmed on location in the Russian Far East wilderness (there are some projection studio shots but they’re pretty unobtrusive), there are some truly amazing setpieces, including an all-timer where Vladimir Arsenyev, the Russian explorer and Dersu must struggle to survive a night in the freezing cold, frantically building a shelter before the night comes and they freeze to death. Not only a terrifically tense set piece, but so gorgeously shot (there are a trio of cinematographers credited) it’s literally gasp-inducing.

WHAT JON THOUGHT: Calling Dersu Uzala a “return to form” for Kurosawa is something of a misnomer, because the film doesn’t carry many of the characteristics you think of when the director’s name springs to mind. This is not shot in black and white, is not shot in Japan, is not edited for speed and is not filled with flashy camera moves. This should not be construed as a complaint, but rather that Kurosawa has created a gorgeous meditation on nature and friendship that expands the director’s film vocabulary.

The color shots of the vast Siberian forest near the film’s beginning already sets the film apart, but that’s just cinematographers Asakazu Nakai, Yuri Gantman, and Fyodor Dobronravov getting started. There are shots of thawing rivers, of moonlit landscapes, and many more wilderness shots that would be perfectly justifiable hanging prints of on a wall. The elements themselves also feature heavily, especially in a memorable sequence in a blizzard where large quantities of grass has to be cut immediately in order to build a shelter. Apparently Mosfilm wanted Toshiro Mifune to star in the picture, and given how he reacted to Red Beard’s strained production, it’s probably for the best that he was not approached for this one.

ANYTHING ELSE, CHRIS? The studios wanted Mifune for the role of Dersu, but I’m so glad they went with Maxim Munzuk, a Tuvan actor. He’s phenomenal in this, and it makes the fact that everyone speaks Russian the entire film make much more sense. His relationship with Yury Solomin who plays Arsenyev feels delicate, but at no time does Kurosawa resort to cheap and easy shots about modern man vs the seemingly “primitive” knowledge of Dersu – they establish his credentials quickly and definitively, and that allows the film to luxuriate in Arsenyev’s adoration of Dersu, his willingness to learn from him, and his despair when he realizes their friendship will not be able to last because of their conflicting worlds. I have a sneaking suspicion the scene where Arsenyev and Uzala reunite, hugging over a downed tree in the forest is something I’ll hold onto for the rest of my life.

ANYTHING ELSE, JON? I want to echo Chris’ thoughts about how easy it would be for the movie, in a worse director’s hands, to resort to offensively broad stereotypes when depicting the differences between Arsenyev and Dersu. It is true that in the end, Dersu’s stay in Arsenyev’s town is short lived, as he’d prefer the forest despite his failing eyesight. However, that really just covers the last 20 minutes of the film. The mutual respect between Arsenyev and Dersu is established quickly, and once established, is never really questioned by Arsenyev or the other soldiers he travels with. The wonder of the wilderness is so well conveyed in the performances (not to mention the cinematography) that the brief time spent in Arsenyev’s house at the end feels as claustrophobic and plain to the audience as it does to Dersu.

THE FINAL WORD(S): For Chris, Dersu Uzala is a hidden high point in the master’s filmography, an exquisitely hushed meditation that deserves a much wider appreciation. For Jon, Dersu Uzala shows that Kurosawa can knock it out of the park without his regular bag of movie making tricks.

NEXT TIME: Out of the wilderness, out of the 70s…Kurosawa gets back to epic samurai films and pierces the veil of illusion and reality with Kagemusha.