On the heels of episode 47 of Cinema Dual, friend of the podcast Stacey sent Jon a found copy of the novelization of Condorman, the movie discussed in that episode. Jon should not have been surprised that a cinematic masterpiece like Condorman would receive the honor of such an ambitious literary adaptation, but nevertheless he was. He had to know more.

On the day I started reading the novelization of Condorman by Joe Claro, I learned that several layers of management were leaving their positions at my job, and that our new director was nowhere to be found. That same week, my car broke down for the sixth time in four months, forcing me to beg coworkers for rides to work and forcing my spouse (whose car I cannot drive) to do all family chores outside the house. In that same month, our American neighbors elected Donald Trump to his 2nd presidential term in a wave of terrifying rhetoric that will have ill effects for everyone. Against that backdrop, I don’t think even a good book would stand a chance, let alone a cheaply made novelization of a movie that is mostly forgotten except as an Easter egg reference in a Pixar short film. But taking fundamentally silly things seriously is what I like to do, so stick with me as I tell you the story of Condorman.

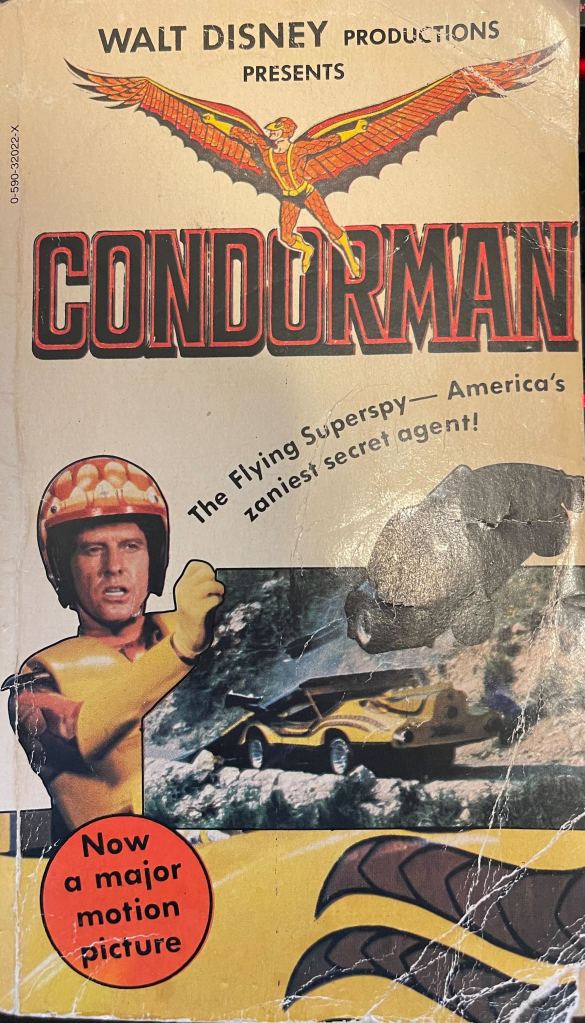

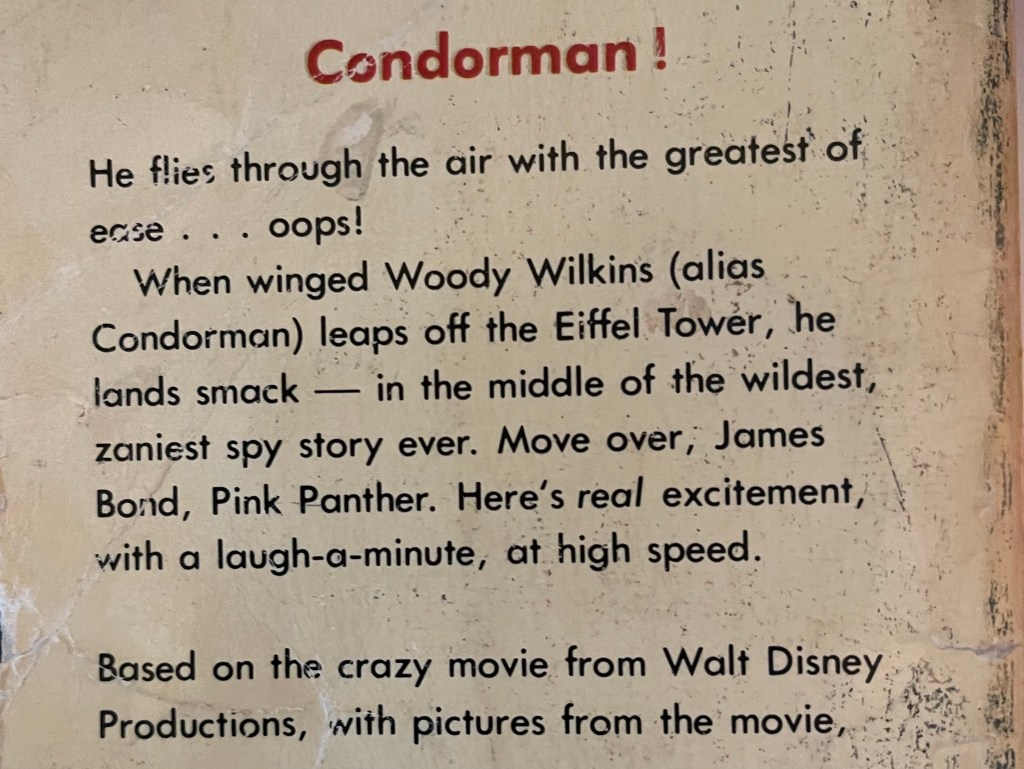

Condorman tells the story of comic book writer/artist Woody Wilkins, a silly man whose obsession making his stories realistic drives him to try and create real life the spy gadgets his heroes use in the comics. While testing his latest creations in Paris, his friend Harry, a file clerk for the CIA, is tasked with finding an American civilian to go on an explicitly unimportant mission to exchange some papers. With no other real prospects, Harry lures Woody into accepting the mission with the promise of real life espionage experience, thus adding more authenticity to his comic books.

The fantasy goes immediately to Woody’s head as he bungles his way through the assignment. He not only completes the mission, but also accidentally foils an assassination, leaving a lasting impression on his contact, KGB agent Natalia Rambova. She herself is on the verge of defecting to the West, and demands that Condorman (the alias that Woody gave her) be the operative to extract her from the clutches of her KGB boss and former lover, Krokov.

From there the adventure takes off as Natalia, Harry, and Woody, armed with zany gadgets inspired by his comics, race through Europe with Krokov and his elite squad the Brochnoviatch on their trail. Both the movie and the book intend for Condorman to be a more comedic take on the James Bond type of adventure. The success in each, or lack thereof, is surprisingly affected by the medium in which you experience the story.

I do not believe the Condorman story has enough going on to merit a serious expansion of the plot and character details. So when author Joe Claro turns Marc Stirdivant’s script into a novel by mostly rewriting script notes into full paragraphs, it is an act of mercy that keeps the proceedings quite short. A character expresses a need to travel to a different country and in the next sentence they have arrived at their destination. If the movie has an action scene that doesn’t really work, it’s summed up in a couple of sentences in the book. You could finish this in a single setting without missing a beat.

And yet, Woody as a character works better in the novel than on screen. You could chalk that up to Michael Crawford’s performance in the film, but in the book, it is made explicit how unserious Woody is meant to be. By the same token, without the need to coordinate an action scene with an actor who can’t do action scenes, Woody’s action moments in the book come off as a little bit more competent.

Conversely, the film’s most iconic character, Krokov, suffers the exact opposite problem in the book by not having Oliver Reed there to elevate the material. If there was a man that Cinema Dual would endorse to perform a public reading of the phone book, it would be Oliver Reed. The man can make an absolute mountain out of the most generic Bond villain nonsense.

Expanding on that Bond thread just a little bit further, the other failure of the book is that it does lack the genuinely good aspects of its Bond homage, namely the European adventuring and the car/boat chases. When we recorded the podcast episode on the movie, one of Chris’ takeaways was that the chases were surprisingly good. By largely sticking to Stirdivant’s script, Claro deprives the book’s plot of the more lively aspects of the finished film.

I must admit there was more to admire about this book than I anticipated going in. The main character does come off better in the novelization than in the actual film. That being said, if there was ever a use case for the phrase “damning with faint praise”, this would 100% be that case. Ultimately the book loses most of the film’s already marginal charms, and can’t be recommended with any amount of sincerity, to the surprise I’m sure of no one.