Something Like a Filmography takes a (brief) look at the filmography of Akira Kurosawa. Twice a month, Chris and Jon share their impressions of each film, both on its own terms and in terms of Kurosawa’s legacy and its intersection in the Cinema Dual hosts’ lives.

FROM THE BOX: Both the final film of this period in which Akira Kurosawa would directly wrestle with the demons of the Second World War and his most literal representation of living in an atomic age, the galvanizing I Live in Fear presents Toshiro Mifune as an elderly, stubborn businessman so fearful of a nuclear attack that he resolves to move his reluctant family to South America. With this mournful film, the director depicts a society emerging from the shadows but still terrorized by memories of the past and anxieties for the future.

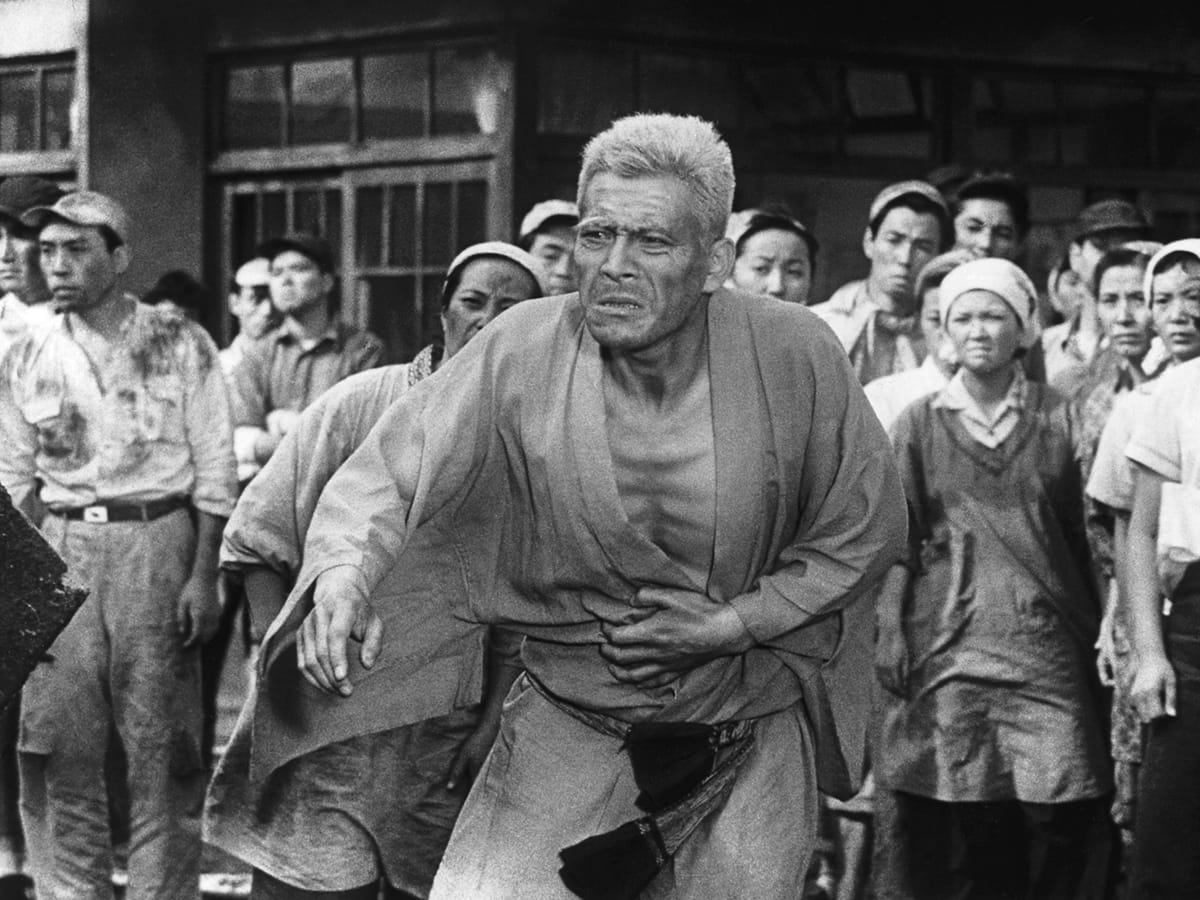

WHAT CHRIS THOUGHT: Also known as Record Of A Living Being, Kurosawa takes a giant left turn away from the ambitious spectacle of Seven Samurai and turns inward, once more (albeit more directly) addressing the fears and concerns of post-war Japan and in particular the very real threat of nuclear annihilation. Not even a decade removed from the dropping of the bomb on Hiroshima and the nuclear testing by the US, Russia, and Britain, Kurosawa forgoes metaphor (no giant lizards here) and builds a very small film where Toshiro Mifune, aged up to be an old man in desperate fear of nuclear war attempts to use his vast wealth as the owner of a ironworks factory to build a fallout shelter and then, in a further bout of paranoia force his family to flee with him to Brazil where he believes they will be safe. The film itself deals with the family’s attempt to rule him mentally incompetent and the very real fallout from that decision.

It’s an admittedly smaller film by design, but the fact that I Live In Fear feels so small is a huge dent against it. Relieved of censors and perhaps riding the biggest wave of popularity he’ll ever have, it’s baffling he would create something so on the nose it feels like a trifle. Mifune actually does a pretty great job playing the increasingly frustrated and delusional Nakajima, a mix of makeup and posture lending weight to his performance. Everyone else, including my beloved Takashi Shimura as the dentist drawn into the family ordeal which raises his own concerns, feels like they’re walking through a rehearsal. There’s definitely something here – not only around nuclear and atomic fears but the role of family, of familial responsibility, and how those ties are strained and broken. But nothing ever comes together or resolves into anything remotely critical, Kurosawa instead laying out in base exposition the film’s themes and using the family dynamics as nothing more than window dressing.

WHAT JON THOUGHT: On the one hand, it is perfectly reasonable that Kurosawa would try to follow up Seven Samurai, then the most expensive Japanese movie to date, with something more modest in scope. Enough time had also passed from the period of Allied censorship boards for Kurosawa to address the threat of nuclear annihilation directly. On the other hand, the resulting I Live In Fear is mostly a series of relatively didactic conversations about the reasonableness (or lack thereof) of Kiichi Nakajima’s decision to force his family to move to the apparent safe haven of Brazil to escape nuclear attacks on Japan. For the artist who made Rashomon, the film’s themes reach only shallow depths given the subject matter.

Consider the casting of Toshiro Mifune in the role of the patriarch Kiichi, against the older Takashi Shimura who is also in the movie but relegated to providing the main voice of support to Kiichi’s eccentric behavior in the character of Dr Harada. We’ve seen Shimura play weak, frail and vulnerable for Kurosawa before. Shimura could have made Kiichi a more relatable figure if given the chance. Indeed, Dr Harada mentions that Kiichi’s concerns are shared by all Japanese and that his actions (up to a point) don’t fit the traditional definitions for classifying someone as incompetent. But Mifune, known for his vigor and rage, plays him like a modern day billionaire trying to escape Earth by colonizing Mars. Mifune’s performance succeeds as a villain, but the tragedy of it feels miscalculated. If Ishiro Honda took all of the anxieties of nuclear annihilation and represented them as a giant monster that posed a real threat to all of Japan, the year after Kurosawa seemingly responded with a man in an asylum who believes he’s watching the Earth burn from the safety of another planet.

ANYTHING ELSE, CHRIS? While I can understand Jon’s view of Mifune as the rich billionaire villain of his own story when viewed through a thoroughly modern post-Musk world (if only that were the literal truth), I never got that feeling from Mifune’s performance. I saw the terror of the old, and the fear and pain of not being able to get your fear across to others, and how that amplifies the pain and anguish. That’s reinforced by the callous nature of his family, who with few exceptions come across as greedy and overly reliant on his wealth. It’s mentioned multiple times why not just let him do what he wants – the family doesn’t have to all go with him. But to do that would mean the loss of their financial grounding, and this conflict in my view muddies the intent of what Kurosawa is trying to get across in the film.

It’s not an entire wash, though. There’s real drama and pain in Eiko Miyoshi’s performance as Nakajima’s wife, who is pressured by her children into formalizing the petition. And there’s a beautiful moment when, despite fighting with his children and having to be in the same room with them during the process, he goes out in the stifling heat and brings everyone back cold sodas. Likewise the two moments Jon mentions below, particularly that striking ending. But it’s too few moments of genius in an otherwise leaden film, drowning in its own melodrama. I understand the genesis for this was a conversation between Kurosawa and his close friend and partner, the composer Fumio Hayasaka, who was dying aha the time. I can give I Live In Fear some small quarter for the reasoning behind its making, but coming as it does after such a monumental film and another masterpiece to follow, it’s still a trifle to my eyes.

ANYTHING ELSE, JON? We do get one moment of insight into the depths of Kiichi’s suffering, in one of the film’s two major bright spots. There’s a small sequence early in the film where the sounds of planes flying overhead are immediately followed by lightning then thunder. Kiichi instinctually rushes over to try and cover his infant grandchild from the blast he assumes is coming, only for the infant to start crying for his mom. The second it takes for the rain to start pouring and for Kiichi to realize that he’s not about to die right then and there is agonizing slow.

The film’s other major highlight is the final shot, whereupon realizing that Kiichi’s mind is gone, Takashi Shimura slowly walks down the hall, turns to go down the stairs, and stops to ponder the weight of what has been lost, before eventually continuing. The length of this shot puts the audience in the same contemplative position as Shimura. If this is the story that Kurosawa wants to tell, it’s a good way to go out.

THE FINAL WORD(S): For both Chris and Jon, I Live In Fear is a functional, if odd, drama that squanders its seemingly infinite thematic potential by being almost too direct in its address.

NEXT TIME: It’s time for the first of Kurosawa’s Shakespeare adaptations with Throne of Blood, so grab your trio of witches and avoid the moving Birnam Wood.

Leave a comment