Something Like a Filmography takes a (brief) look at the filmography of Akira Kurosawa. Twice a month, Chris and Jon share their impressions of each film, both on its own terms and in terms of Kurosawa’s legacy and its intersection in the Cinema Dual hosts’ lives.

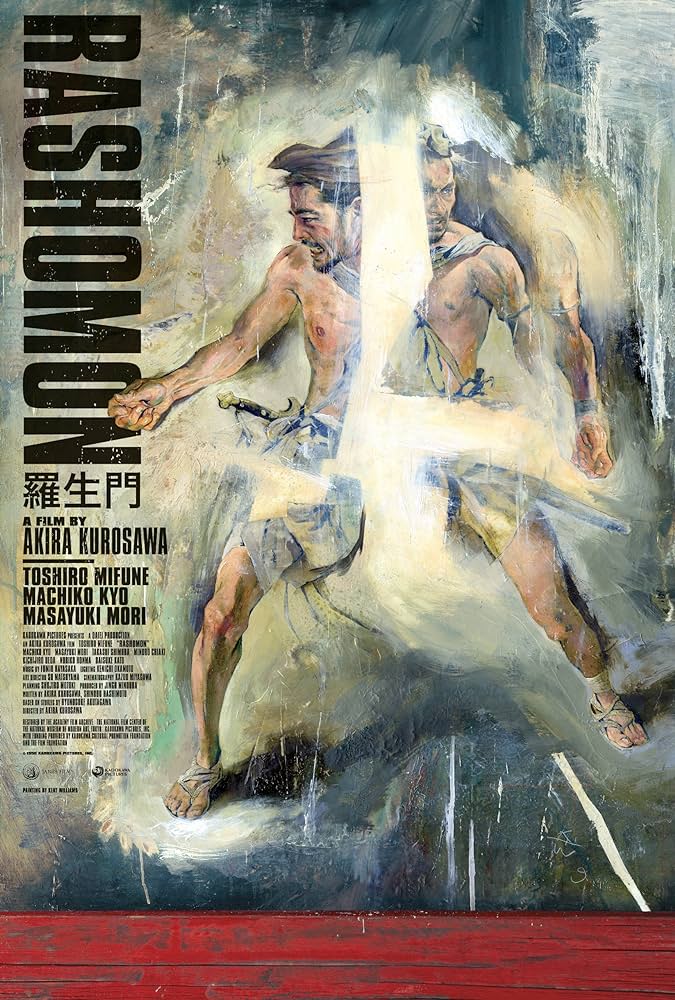

FROM THE BOX: A riveting psychological thriller that investigates the nature of truth and the meaning of justice, Rashomon is widely considered one of the greatest films ever made. Four people give different accounts of a man’s murder and the rape of his wife, which director Akira Kurosawa presents with striking imagery and an ingenious use of flashbacks. This eloquent masterwork and international sensation revolutionized film language and introduced Japanese cinema—and a commanding new star by the name of Toshiro Mifune—to the Western world.

WHAT CHRIS THOUGHT:Talk about a leap. Released in the same year, the change both on a story level and a visual level from Scandal to Rashomon is astounding. Necessity being the mother of invention, the paltry budget given to Kurosawa by Daiei results in some of the most beautiful shots of Kurosawa’s career, from the forest scenes with the dappled light shining through the trees onto our characters, to the sublime use of depth throughout the film, Kurosawa finding every opportunity to contrast his scenes using foreground and background elements. From canted angles showing ruins in the foreground as we see the Rashomon Gate where our story will take place (it ALL takes place at the gate, another brilliant storytelling device) to the gorgeous shots of Mifune’s bandit and Machiko Kyō’s wife running through the forest, their bodies in focused by blurred by the motion blur of the rushing branches and leaves, creating ethereal effects across their bodies.

And then there’s the story, and those performances. We may have thought we witnessed Toshiro Mifune unleashed as early as Drunken Angel, but it’s here where we see the man practically invent his future persona on the spot. The wisdom of framing the story as a campfire tale, fracturing the narrative into four very unreliable streams from the woodcutter, the bandit, the wife, and the samurai (through a frickin’ medium…how great is this movie?!) Kurosawa beautifully modernizes cinematic storytelling while simultaneously commenting on how we instill our own versions of the “truth” when discussing a film.

Huh, kinda like the whole framework of this podcast, ya think?

WHAT JON THOUGHT: As the film starts, from the introduction at the Rashomon gate where the priest and woodcutter have to be cajoled out of their stupor by the commoner, you can tell that something already feels different. There is no neorealism to be found in Rashomon. While pragmatically constrained by a tight budget, Kurosawa chooses to focus the story in three main locations, each of which stylized to maximum affect. There’s the gate where the rain and ruin amplify the despair experienced by those there; the forest, where things are always obscured and in motion; and the court, where the participants are neatly organized to present their testimonies.

Each of these three are vividly brought to life by cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa, who recounts being given a lot of free rein by Kurosawa (who was eager to work with him) to experiment with shot composition. The audacious tracking shot of the woodcutter entering the forest may not advance the plot, but does draw you into the world of the movie. Kurosawa and Miyagawa draw on silent film’s visual storytelling to enhance the dialog spoken by the actors. It’s one thing for the bandit to describe the woman’s beauty, but quite another to see him silently reacting to seeing her for the first time. And the most famous visual elements of the film, the filming of the sun and the shadows on the actors faces rightly deserve all the accolades they’ve received.

ANYTHING ELSE, CHRIS? I want to touch on something Jon said above, about the lengthy tracking shot of the woodcutter entering the forest. As I was watching this again that scene stood out to me, and I was asking myself “Why is Kurosawa taking so long with this shot?” He’s never been a careless filmmaker, so rather than just go with my initial impatience, I breathed in, relaxed, watched and thought. There’s a reason: the filmmakers watched this during editing and said “yeah, that’s just right.” Reading back Jon’s initial thoughts about that scene, and the way it draws you into not only the mystery at the heart of the movie but the entire world Kurosawa is creating hit me like a lightning bolt. I went back and watched again and that sequence completely opened up for me in a way it never did before. Serves me right, considering how much I go on about intent…

Beyond that, I want to take another moment to shower more praise on the script and Takashi Shimura’s performance. I love how it’s the woodcutter that brings us into the mystery, setting himself of as kind of the impartial witness, leading us to believe that in a sea of unreliable narrators as the story plays out from the different viewpoints, we don’t consider the one character who set the whole thing up, which makes it doubly delicious when in the end of the mystery of the missing dagger is revealed and the woodcutter stands as perhaps the most guilty of misleading the audience. Simply superb on every level.

ANYTHING ELSE, JON? All of the stunning cinematography can only get you so far if it’s not in service of a story worth telling, and I really want to emphasize how Kurosawa and Hashimoto structure and weave the theme into the film. The actual facts of what happened constitute the first and least accessible layer of reality. The contradictory testimonies given at the court exist in a more accessible layer. Even those are only relayed to us by the woodcutter and the priest in conversation with the commoner in their own third reality, which we can’t still fully trust because the woodcutter is caught in a lie, however innocuous it may seem. The fact that the term “Rashomon effect” has become common parlance for “unreliable narrator” should be enough evidence for the film’s success on this front.

And finally, a well crafted and intricate script wouldn’t be much use without a core group of actors that have enough range to do what the movie requires. Toshiro Mifune of course stands out for his outsized portrayal of the bandit, but even within that register at times he can go from raging animal (at times he was literally told to act like a lion) to scolded child. Masayuki Mori as the dead samurai may not have as much to do, but he ably steps up to the plate, especially in the frozen cold stare he gives his wife in one of the recollections. For acting in this movie however, I believe that the most impressive performance goes to Machiko Kyo as the wife. Since most of the conflict stems around her various reactions to the bandit’s assault, she has to alternately play Masago as a devoted wife, a psychotic mastermind, and various shades in between. It is encouraging to see that Kyo had a prolific acting career for decades after this.

THE FINAL WORD(S): For Jon, Rashomon is the first Kurosawa movie so far to have absolutely no wrong notes on any level of production. Everything comes together perfectly. Chris is 100% in alignment, and will simply add that he (I? Perspective’s a funny thing, huh?) can’t wait to get another viewing in. But that will have to wait because…

NEXT TIME: We take small step between giants as Kurosawa adapts Dostoevsky’s minor masterwork about a benevolent fool in The Idiot.

Glad you enjoyed it so much. Every time I watch it I’m still left in awe at what Kurosawa achieved here. This one changed cinema forever and ensured that Western audiences finally started paying attention to Japanese cinema.

LikeLike