Something Like a Filmography takes a (brief) look at the filmography of Akira Kurosawa. Twice a month, Chris and Jon share their impressions of each film, both on its own terms and in terms of Kurosawa’s legacy and its intersection in the Cinema Dual hosts’ lives.

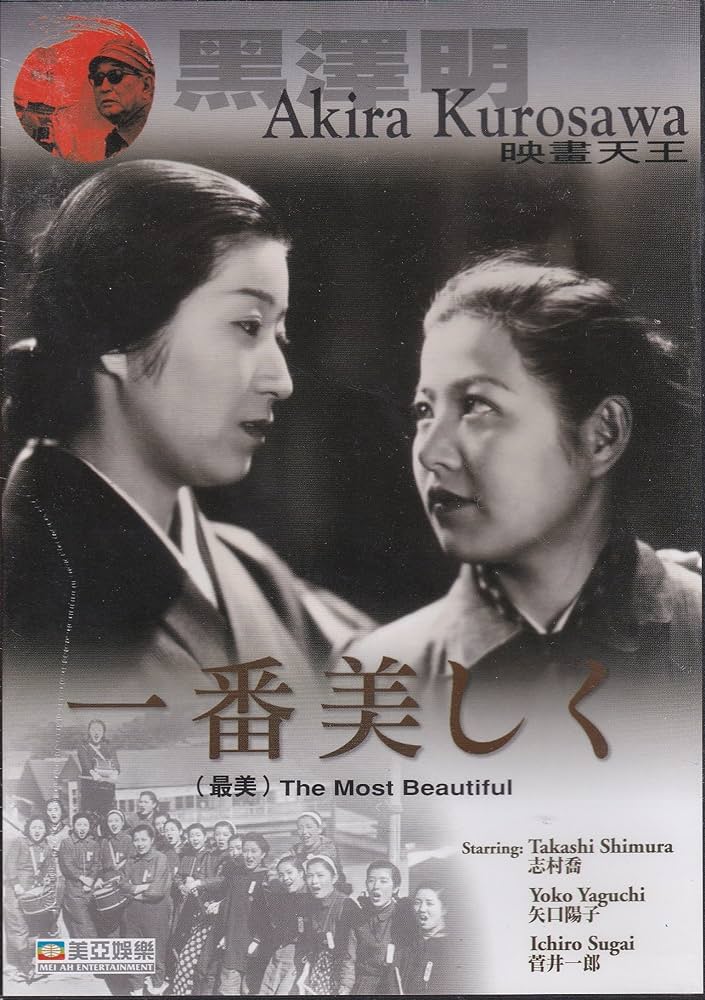

FROM THE BOX: This portrait of female volunteer workers at an optics plant during World War II, shot on location at the Nippon Kogaku factory, was created with a patriotic agenda. Yet thanks to Akira Kurosawa’s groundbreaking semidocumentary approach, The Most Beautiful is a revealing look at Japanese women of the era and anticipates the aesthetics of Japanese cinema’s postwar social realism.

WHAT CHRIS THOUGHT: This is a tough one. Trying to watch The Most Beautiful with the knowledge of how the war ends, as someone whose country was the target of the propaganda, I was constantly shifting to try and understand not only the movie’s intent (which seems really to be nothing more than patriotic pot stirring to lift spirits during the war – something the US is also certainly guilty of as well), and Kurosawa’s execution. Ultimately I think the film - while beautiful to look at – fails with too much manufactured drama and indecision. That indecision is the part I struggle with the most, as it’s hard to identify when Kurosawa is siding with the fervor of building what amounts to weapons of war, or commenting on the cost these woman pay in the name of patriotism. And the struggle goes even further, as I have to question how guilty I am of making assumptions as to Kurosawa’s political ideology, so until I do a little reading for my second section I’ll focus on the filming itself, which is just as solid as his debut even as it’s in the service of what amounts to a lesser story. There are sublime moments, such as the joy he brings to the volleyball sequences, the sequence of the girls eagerly waiting for a train to pass that’s separating them from Yamazaki, a young woman who fell off a rooftop and is now on crutches, desperately eager to get back to work. Kurosawa also manages to be 2 for 2 for sticking the landing on his endings, as the meaning of “The Most Beautiful” comes to life in the sacrifice for a greater cause in light of a devastating tragedy.

WHAT JON THOUGHT: In a recent episode of Cinema Dual, I talked about how I’m a sucker for dizzyingly large coordinated crowd shots in movies, especially pre-CGI ones. The coordination of the women’s group of workers ends up being consistently the most visually compelling element of The Most Beautiful, which isn’t hard when its competition in that regard ends up being a productivity chart. The shot of the woman in the garden staring at the moonlit mountain is the one shot where I felt like I was watching a Kurosawa movie. The plot itself suffers along similar lines where in small moments, Kurosawa tries to mine some drama out of the negative effects the increased production quotas have on the women. However, the bulk of the movie is so swallowed up by its propaganda (“Attack and destroy the enemy” is literally the opening frame of the movie) that Kurosawa’s interests can’t really shift the message too much.

ANYTHING ELSE, CHRIS? Coming back again to the work of Donald Richie, I’m struck by how Kurosawa frames this obviously scripted film with professional actors as a documentary, and how he further develops his cinematic language here. Working within the confines of his country’s national policy, he still finds the humanity and drama in his subject, first by clearly setting up the stakes (the women asking to raise their quota to 66% instead of 50%) and then seeing how duty and national pride slowly tear away at their health, their compassion, and their sense of identity. The constant use of the parade as a segue to another section, the way he chops up the editing for his more kinetic sequences like the volleyball game, and how when it’s played a second time he slows that rhythm down to indicate their exhaustion. Richie mentions Japan’s influence of German and Russian documentary making, and in the consistent focus on people and faces Kurosawa takes those influences and makes them his own. The flashback sequence, where we see the events that lead to the search for the lens, is another breakout moment Kurosawa would return to again and again in his later films, using the flashback as a cause and effect tool rather than indulging in a false sense of nostalgia. Not a documentary by our modern sensibilities, but in using film language to document something more than a simple event Kurosawa – unsurprisingly – manages to elevate the entire enterprise.

ANYTHING ELSE, JON? As Chris mentioned wanting to avoid making further speculations on Kurosawa’s own relation to the politics of this movie (and larger war efforts) without more research, instead I’ll just focus on my own relation to the movie’s messaging. Propaganda isn’t uniquely Japanese of course, and I’ve enjoyed similar movies like Powell and Pressburger’s 49th Parallel. More overtly grotesque aspects like the sexism around the womens’ quotas, or the xenophobic marching songs are present but mostly sidelined. What the film dwells on how productivity is tied to moral character. Anyone who has ever worked a job where they’ve been told how merely performing the expectations written into the job contract is insufficient will recognize the messaging on display here. Employees must devote their whole lives to the company in service of a more noble calling. The line that sticks with me from this movie is when someone says that their lenses “might” (emphasis mine) be in the fighter planes flying overhead currently, because they can only speculate that their increased efforts are actually helping the war.

THE FINAL WORD(S): For Chris, The Most Beautiful works for its genuine personal moments of humanity, which Kurosawa makes clear enough so it’s easier to overlook the obvious propaganda, although a revisit of the film wouldn’t be on the docket any time soon. For Jon, it’s sort of the inverse: while there are clearly parts that work and parts that don’t, the parts that do are overshadowed. Again, no plans to revisit.

NEXT TIME: We return to the inner struggle and physical conflict of judo vs. jujitsu with Sanshiro Sugata Part 2.

Leave a comment